On any average day in 2021, around 232,000 shared electric vehicles took to the streets in cities across Canada, the U.S., and Mexico.

Just the year prior in 2020, major media outlets rang the death knell for shared micromobility in general and scooters in particular during the worst months of the COVID-19 pandemic.

For a few months during the pandemic, it seemed as if the micromobility industry – which had held out so much promise for transforming transportation – might collapse.

Micromobility Growth, Despite Losses

Although personal electric vehicles offered the best way to socially distance while commuting, lockdowns and closures put commutes on such hiatus that air pollution started disappearing along with sectors of the economy.

Now that the worst is behind us and the data is in, we can see how the micromobility industry rebounded after that seeming collapse. At least in North America, the shared bike and scooter industry showed considerable resilience in the face of 2020’s losses, bouncing back strongly.

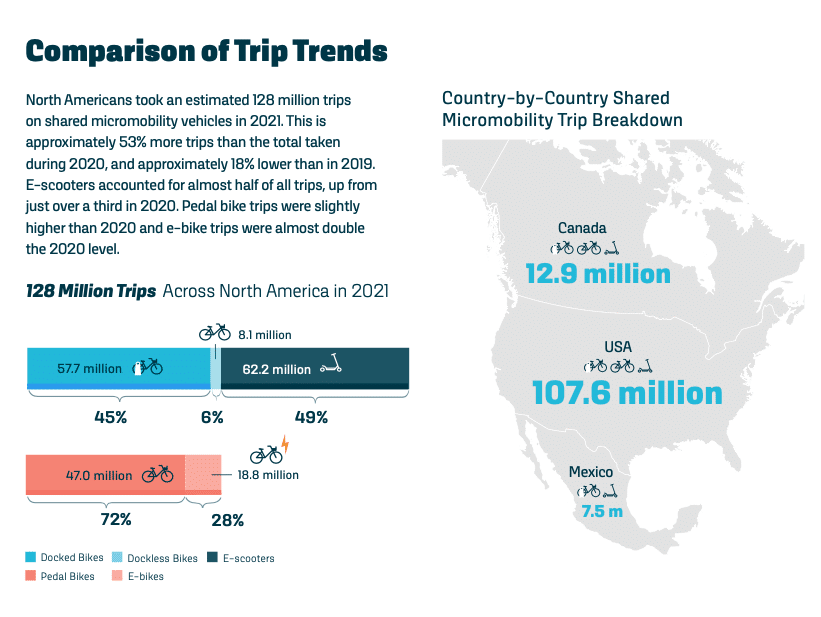

Last year, NABSA, the North American Bikeshare and Scootershare Association, released its 2021 state of the industry report to show how shared micromobility fared. The report details how the industry not only recovered but also exceeded 2019 levels of ridership by 20% at the year’s end, a rise of about 40% over ridership at the end of 2020.

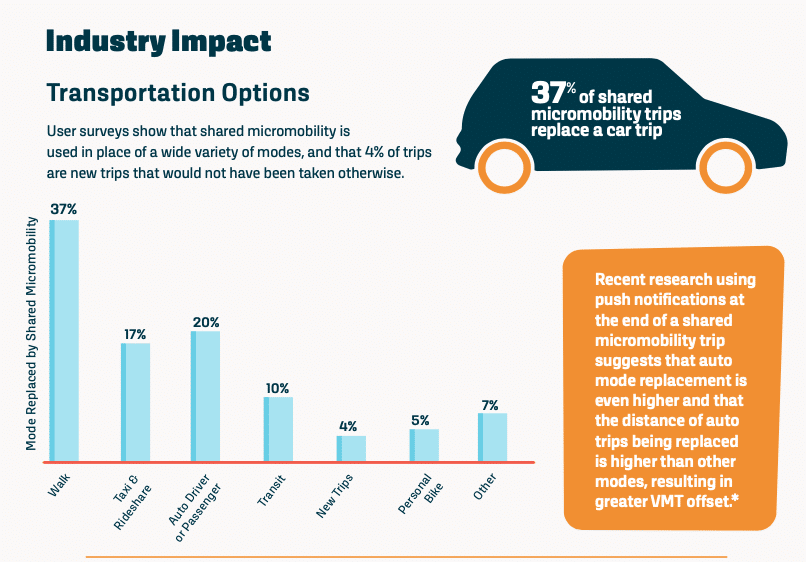

The industry not only grew in riders but also expanded into new cities in 2021, with 74 cities adding either a bikeshare or electric scooter share system and 25 cities adding both. Overall, both ebike and e scooter trips replaced car trips about 37% of the time, with riders traveling longer distances on trips that would otherwise involve a car.

Riders who own their own scooters are likely to travel even longer distances than those who share, since owners are able to charge their own vehicles and don’t keep paying by the hour for their ride.

Once Again: Micromobility Isn’t a Fad

What does all this mean in 2023?

For one thing, it means there is a desire for alternative forms of transportation in cities all over North America. That desire can’t even be quelled by a global viral outbreak.

Sharing meets a lot of the demand, but creates its own problems. For those who can afford it, we think owning an ebike or e scooter is the better option, given the environmental costs of the sharing economy and the fact that owners tend to use their PEVs much more often to replace car trips.

If you can’t afford to pay full price for an electric scooter, you can lease one. Subscribe to the Unagi Model One for a small setup fee of $50, and receive a brand new scooter with warranty and theft insurance for $50-$60/month. This is comparable to renting a scooter for the daily commute, but you’ll always have a reliable scooter with you, and you won’t have to worry if there’ll be one available when you leave the office.

Even after the worst of the pandemic, as businesses opened and lockdowns ended, local agencies continued to incentivize micromobility and make room for smaller vehicles with “slow streets” initiatives, increased bike lanes, and other infrastructure changes that benefit everyone from pedestrians, to cyclists, to ebike and e scooter riders. Hundreds of miles of bike lanes have been built in U.S. cities over the past couple years.

In too many ways to count, the pandemic became a stress test for every industry, forcing businesses to change and adapt to a quickly changing world. However, when it came to micromobility, we saw a large part of the world change and adapt to personal electric vehicles. That’s a good sign, one that indicates electric scooters are here to stay – at least, that is, in North America.

Read and download the full NABSA report here.